For many of us, just hearing the word subtext gives us a flashback to our high school English class. In that class, the teacher probably discussed subtext in terms of dialogue and left it at that. But, subtext really refers to all that is not spoken and encompasses much more than simply dialogue. Subtext is important in all genres but works slightly differently in each.

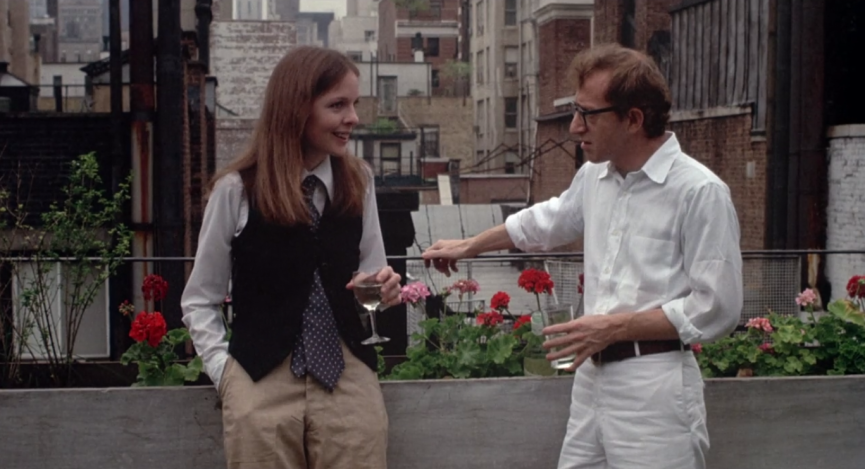

Diane Keaton and Woody Allen make small talk in Annie Hall. Courtesy United Artists.

COMEDY

A great example of comedic subtext is the famous subtitled scene in Annie Hall. This scene illustrates one of the fundamental questions a screenwriter needs to ask when writing any scene. How does the character wish to present themselves? and What is the reality of the character? Typically the tension in any scene exists in the gap between those two questions. In this scene about two people flirting and setting up a date, you very clearly see their attempts to present themselves as intelligent, interesting people in the dialogue while the subtitles show their actual doubt and much lower self-esteem. You can see the scene here.

Enroll in ScreenwritingU’s Subtext class for 50% off — Starts July 7

An important element of subtext is that the audience knows either what the characters aren’t saying or has information that only some of the characters have. This is crucial in what I’d call magical comedies, films where the main character is Big or 17 Again or 13 Going on 30. The character—through some form of magic—is somehow not as they seem. And this gap between what the character knows and what the other characters don’t propels not only the plot but all of the jokes.

In Ordinary People Mary Tyler Moore doesn’t know what to say to her son, Timothy Hutton. Courtesy Paramount Pictures.

DRAMA

On the drama side, there’s a terrific scene in Ordinary People that demonstrates how you can take the most mundane situation, a family a breakfast, and, through subtext, give it great tension. Here again, you see characters whose outward goals and true selves conflict. Each character in this scene is attempting to be “good” in their role, Beth (Mary Tyler Moore) wants to be a good mother, Calvin (Donald Sutherland) a good father and Conrad (Timothy Hutton) a good son. However, the dual tragedies they’ve suffered stand in the way of being able to successfully navigate anything including a simple breakfast. You can see the scene here.

THEME

Theme can be thought of as a form of subtext since it is something that the writer should not directly state. To illustrate this, consider that all superhero movies have the same theme. The outsider, or other, uses the very thing that makes them an outsider to bring justice to the world. Whether we’re talking about an alien (Superman), an orphan (Batman) or a mutant (Spider-Man) we’re talking about someone on the outside of our society, someone who is typically shunned, who uses their uniqueness to save us all. While these films often get bogged down with special effects and over-long fight scenes, they’re at their best when they’re mining their themes.

Superman the other who saves the day. Photo courtesy Warner Brothers.

ALLEGORY

Subtext, via theme and allegory, can also be political reflecting what’s going on in the world around us. One of the most famous examples of this is Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, the play about a very real witch hunt was inspired by the metaphoric witch hunts of the McCarthy era. It was not made into a film however until 1996 demonstrating that while a film can have an immediate allegoric impact, it must have a strong universal theme to survive the cycles of history.

As an experiment, pick one of your favorite film scenes and write down everything that’s not being explicitly said or shown. Then think about how you know these things and ask yourself how the writer conveyed them.